Why the central problem in neuroscience is mirrored in physics.

The nature of consciousness seems to be unique among scientific puzzles. Not only do neuroscientists have no fundamental explanation for how it arises from physical states of the brain, we are not even sure whether we ever will. Astronomers wonder what dark matter is, geologists seek the origins of life, and biologists try to understand cancer—all difficult problems, of course, yet at least we have some idea of how to go about investigating them and rough conceptions of what their solutions could look like. Our first-person experience, on the other hand, lies beyond the traditional methods of science. Following the philosopher David Chalmers, we call it the hard problem of consciousness.

But perhaps consciousness is not uniquely troublesome. Going back to Gottfried Leibniz and Immanuel Kant, philosophers of science have struggled with a lesser known, but equally hard, problem of matter. What is physical matter in and of itself, behind the mathematical structure described by physics? This problem, too, seems to lie beyond the traditional methods of science, because all we can observe is what matter does, not what it is in itself—the “software” of the universe but not its ultimate “hardware.” On the surface, these problems seem entirely separate. But a closer look reveals that they might be deeply connected.

Consciousness is a multifaceted phenomenon, but subjective experience is its most puzzling aspect. Our brains do not merely seem to gather and process information. They do not merely undergo biochemical processes. Rather, they create a vivid series of feelings and experiences, such as seeing red, feeling hungry, or being baffled about philosophy. There is something that it’s like to be you, and no one else can ever know that as directly as you do.

Our own consciousness involves a complex array of sensations, emotions, desires, and thoughts. But, in principle, conscious experiences may be very simple. An animal that feels an immediate pain or an instinctive urge or desire, even without reflecting on it, would also be conscious. Our own consciousness is also usually consciousness of something—it involves awareness or contemplation of things in the world, abstract ideas, or the self. But someone who is dreaming an incoherent dream or hallucinating wildly would still be conscious in the sense of having some kind of subjective experience, even though they are not conscious of anything in particular.

Philosophers and neuroscientists often assume that consciousness is like software, whereas the brain is like hardware.

Where does consciousness—in this most general sense—come from? Modern science has given us good reason to believe that our consciousness is rooted in the physics and chemistry of the brain, as opposed to anything immaterial or transcendental. In order to get a conscious system, all we need is physical matter. Put it together in the right way, as in the brain, and consciousness will appear. But how and why can consciousness result merely from putting together non-conscious matter in certain complex ways?

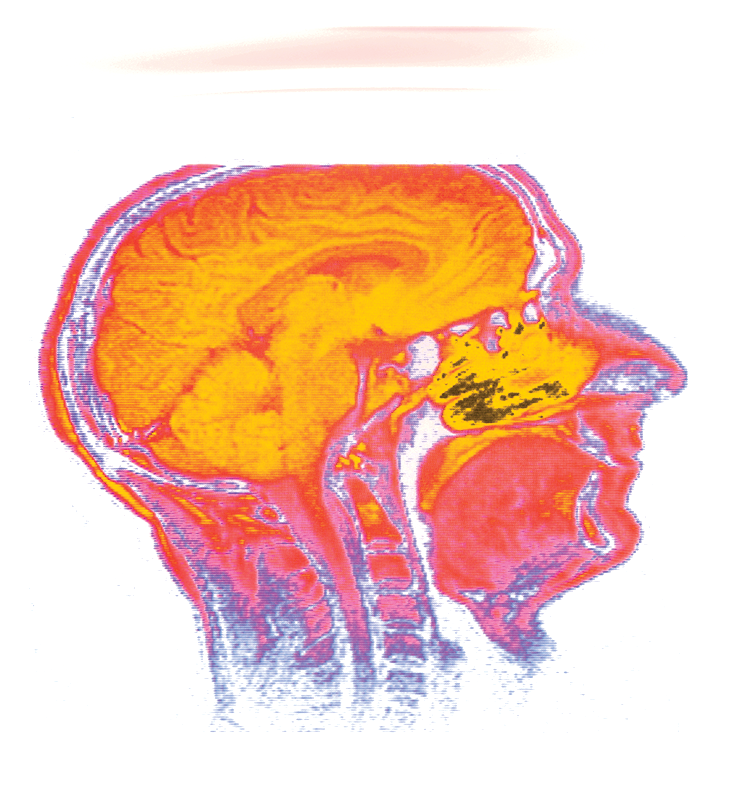

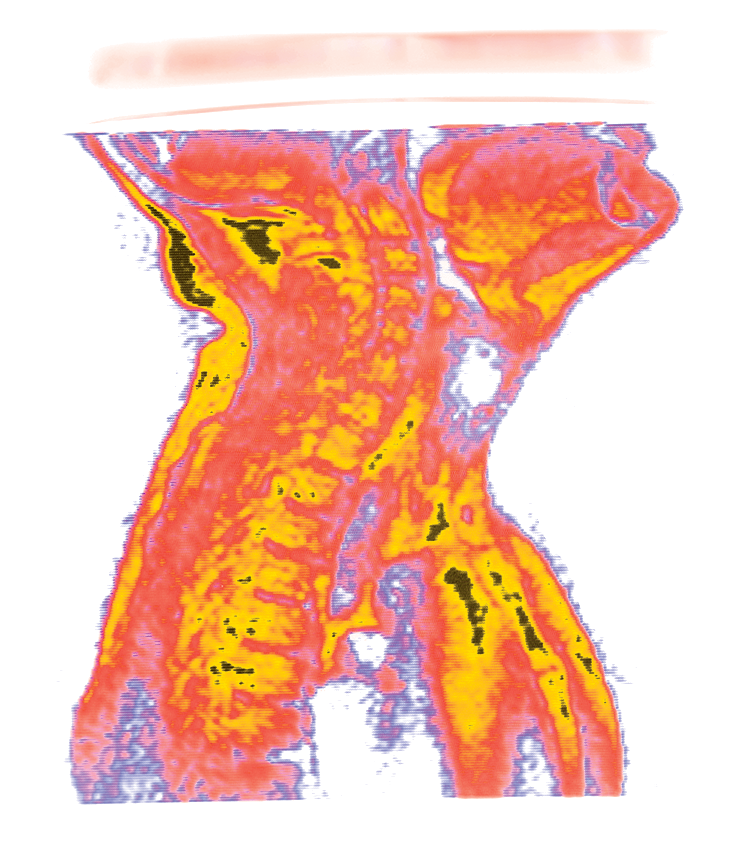

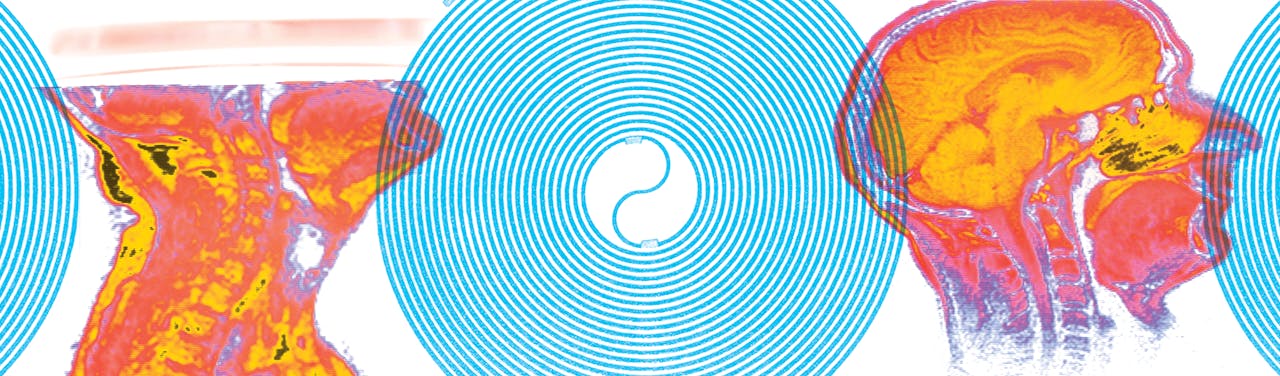

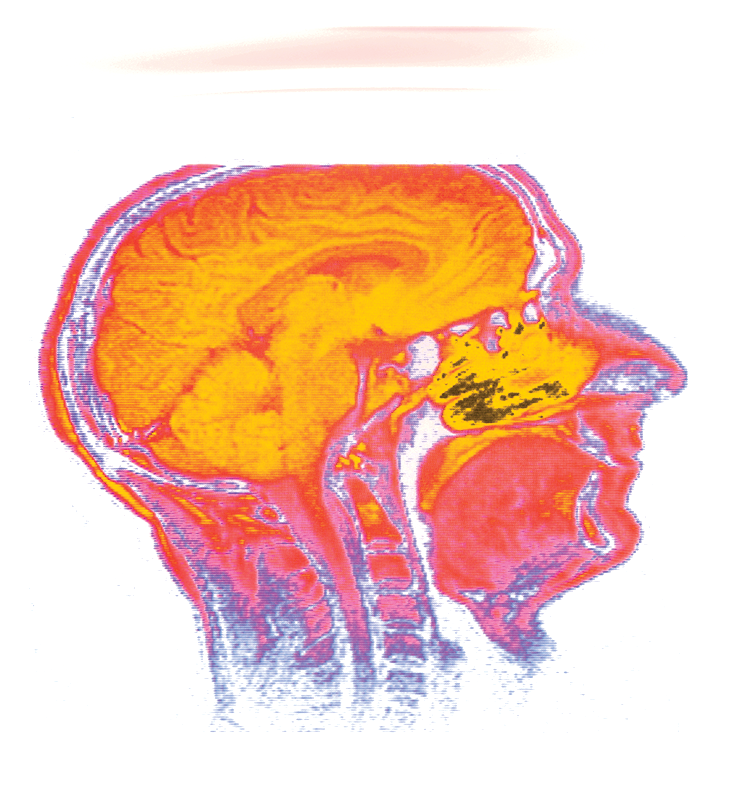

This problem is distinctively hard because its solution cannot be determined by means of experiment and observation alone. Through increasingly sophisticated experiments and advanced neuroimaging technology, neuroscience is giving us better and better maps of what kinds of conscious experiences depend on what kinds of physical brain states. Neuroscience might also eventually be able to tell us what all of our conscious brain states have in common: for example, that they have high levels of integrated information (per Giulio Tononi’s Integrated Information Theory), that they broadcast a message in the brain (per Bernard Baars’ Global Workspace Theory), or that they generate 40-hertz oscillations (per an early proposal by Francis Crick and Christof Koch). But in all these theories, the hard problem remains. How and why does a system that integrates information, broadcasts a message, or oscillates at 40 hertz feel pain or delight? The appearance of consciousness from mere physical complexity seems equally mysterious no matter what precise form the complexity takes.

Nor would it seem to help to discover the concrete biochemical, and ultimately physical, details that underlie this complexity. No matter how precisely we could specify the mechanisms underlying, for example, the perception and recognition of tomatoes, we could still ask: Why is this process accompanied by the subjective experience of red, or any experience at all? Why couldn’t we have just the physical process, but no consciousness?

Other natural phenomena, from dark matter to life, as puzzling as they may be, don’t seem nearly as intractable. In principle, we can see that understanding them is fundamentally a matter of gathering more physical detail: building better telescopes and other instruments, designing better experiments, or noticing new laws and patterns in the data we already have. If we were somehow granted knowledge of every physical detail and pattern in the universe, we would not expect these problems to persist. They would dissolve in the same way the problem of heritability dissolved upon the discovery of the physical details of DNA. But the hard problem of consciousness would seem to persist even given knowledge of every imaginable kind of physical detail.

In this way, the deep nature of consciousness appears to lie beyond scientific reach. We take it for granted, however, that physics can in principle tell us everything there is to know about the nature of physical matter. Physics tells us that matter is made of particles and fields, which have properties such as mass, charge, and spin. Physics may not yet have discovered all the fundamental properties of matter, but it is getting closer.

Yet there is reason to believe that there must be more to matter than what physics tells us. Broadly speaking, physics tells us what fundamental particles do or how they relate to other things, but nothing about how they are in themselves, independently of other things.

Charge, for example, is the property of repelling other particles with the same charge and attracting particles with the opposite charge. In other words, charge is a way of relating to other particles. Similarly, mass is the property of responding to applied forces and of gravitationally attracting other particles with mass, which might in turn be described as curving spacetime or interacting with the Higgs field. These are also things that particles do or ways of relating to other particles and to spacetime.

Conscious experiences are just the kind of things that physical structure could be the structure of.

In general, it seems all fundamental physical properties can be described mathematically. Galileo, the father of modern science, famously professed that the great book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. Yet mathematics is a language with distinct limitations. It can only describe abstract structures and relations. For example, all we know about numbers is how they relate to the other numbers and other mathematical objects—that is, what they “do,” the rules they follow when added, multiplied, and so on. Similarly, all we know about a geometrical object such as a node in a graph is its relations to other nodes. In the same way, a purely mathematical physics can tell us only about the relations between physical entities or the rules that govern their behavior.

One might wonder how physical particles are, independently of what they do or how they relate to other things. What are physical things like in themselves, or intrinsically? Some have argued that there is nothing more to particles than their relations, but intuition rebels at this claim. For there to be a relation, there must be two things being related. Otherwise, the relation is empty—a show that goes on without performers, or a castle constructed out of thin air. In other words, physical structure must be realized or implemented by some stuff or substance that is itself not purely structural. Otherwise, there would be no clear difference between physical and mere mathematical structure, or between the concrete universe and a mere abstraction. But what could this stuff that realizes or implements physical structure be, and what are the intrinsic, non-structural properties that characterize it? This problem is a close descendant of Kant’s classic problem of knowledge of things-in-themselves. The philosopher Galen Strawson has called it the hard problem of matter.

It is ironic, because we usually think of physics as describing the hardware of the universe—the real, concrete stuff. But in fact physical matter (at least the aspect that physics tells us about) is more like software: a logical and mathematical structure. According to the hard problem of matter, this software needs some hardware to implement it. Physicists have brilliantly reverse-engineered the algorithms—or the source code—of the universe, but left out their concrete implementation.

The hard problem of matter is distinct from other problems of interpretation in physics. Current physics presents puzzles, such as: How can matter be both particle-like and wave-like? What is quantum wavefunction collapse? Are continuous fields or discrete individuals more fundamental? But these are all questions of how to properly conceive of the structure of reality. The hard problem of matter would arise even if we had answers to all such questions about structure. No matter what structure we are talking about, from the most bizarre and unusual to the perfectly intuitive, there will be a question of how it is non-structurally implemented.

Indeed, the problem arises even for Newtonian physics, which describes the structure of reality in a way that makes perfect intuitive sense. Roughly speaking, Newtonian physics says that matter consists of solid particles that interact either by bumping into each other or by gravitationally attracting each other. But what is the intrinsic nature of the stuff that behaves in this simple and intuitive way? What is the hardware that implements the software of Newton’s equations? One might think the answer is simple: It is implemented by solid particles. But solidity is just the behavior of resisting intrusion and spatial overlap by other particles—that is, another mere relation to other particles and space. The hard problem of matter arises for any structural description of reality no matter how clear and intuitive at the structural level.

Like the hard problem of consciousness, the hard problem of matter cannot be solved by experiment and observation or by gathering more physical detail. This will only reveal more structure, at least as long as physics remains a discipline dedicated to capturing reality in mathematical terms.

Might the hard problem of consciousness and the hard problem of matter be connected? There is already a tradition for connecting problems in physics with the problem of consciousness, namely in the area of quantum theories of consciousness. Such theories are sometimes disparaged as fallaciously inferring that because quantum physics and consciousness are both mysterious, together they will somehow be less so. The idea of a connection between the hard problem of consciousness and the hard problem of matter could be criticized on the same grounds. Yet a closer look reveals that these two problems are complementary in a much deeper and more determinate way. One of the first philosophers to notice the connection was Leibniz all the way back in the late 17th century, but the precise modern version of the idea is due to Bertrand Russell. Recently, contemporary philosophers including Chalmers and Strawson have rediscovered it. It goes like this.

The hard problem of matter calls for non-structural properties, and consciousness is the one phenomenon we know that might meet this need. Consciousness is full of qualitative properties, from the redness of red and the discomfort of hunger to the phenomenology of thought. Such experiences, or “qualia,” may have internal structure, but there is more to them than structure. We know something about what conscious experiences are like in and of themselves, not just how they function and relate to other properties.

For example, think of someone who has never seen any red objects and has never been told that the color red exists. That person knows nothing about how redness relates to brain states, to physical objects such as tomatoes, or to wavelengths of light, nor how it relates to other colors (for example, that it’s similar to orange but very different from green). One day, the person spontaneously hallucinates a big red patch. It seems this person will thereby learn what redness is like, even though he or she doesn’t know any of its relations to other things. The knowledge he or she acquires will be non-relational knowledge of what redness is like in and of itself.

This suggests that consciousness—of some primitive and rudimentary form—is the hardware that the software described by physics runs on. The physical world can be conceived of as a structure of conscious experiences. Our own richly textured experiences implement the physical relations that make up our brains. Some simple, elementary forms of experiences implement the relations that make up fundamental particles. Take an electron, for example. What an electron does is to attract, repel, and otherwise relate to other entities in accordance with fundamental physical equations. What performs this behavior, we might think, is simply a stream of tiny electron experiences. Electrons and other particles can be thought of as mental beings with physical powers; as streams of experience in physical relations to other streams of experience.

Manuel Litran / Paris Match via Getty Images

This idea sounds strange, even mystical, but it comes out of a careful line of thought about the limitations of science. Leibniz and Russell were determined scientific rationalists—as evidenced by their own immortal contributions to physics, logic, and mathematics—but equally deeply committed to the reality and uniqueness of consciousness. They concluded that in order to give both phenomena their proper due, a radical change of thinking is required.

And a radical change it truly is. Philosophers and neuroscientists often assume that consciousness is like software, whereas the brain is like hardware. This suggestion turns this completely around. When we look at what physics tells us about the brain, we actually just find software—purely a set of relations—all the way down. And consciousness is in fact more like hardware, because of its distinctly qualitative, non-structural properties. For this reason, conscious experiences are just the kind of things that physical structure could be the structure of.

Given this solution to the hard problem of matter, the hard problem of consciousness all but dissolves. There is no longer any question of how consciousness arises from non-conscious matter, because all matter is intrinsically conscious. There is no longer a question of how consciousness depends on matter, because it is matter that depends on consciousness—as relations depend on relata, structure depends on realizer, or software on hardware.

One might object that this is plain anthropomorphism, an illegitimate projection of human qualities on nature. After all, why do we think that physical structure needs some intrinsic realizer? Is it not because our own brains have intrinsic, conscious properties, and we like to think of nature in familiar terms? But this objection does not hold. The idea that intrinsic properties are needed to distinguish real and concrete from mere abstract structure is entirely independent of consciousness. Moreover, the charge of anthropomorphism can be met by a countercharge of human exceptionalism. If the brain is indeed entirely material, why should it be so different from the rest of matter when it comes to intrinsic properties?

This view, that consciousness constitutes the intrinsic aspect of physical reality, goes by many different names, but one of the most descriptive is “dual-aspect monism.” Monism contrasts with dualism, the view that consciousness and matter are fundamentally different substances or kinds of stuff. Dualism is widely regarded as scientifically implausible, because science shows no evidence of any non-physical forces that influence the brain.

Monism holds that all of reality is made of the same kind of stuff. It comes in several varieties. The most common monistic view is physicalism (also known as materialism), the view that everything is made of physical stuff, which only has one aspect, the one revealed by physics. This is the predominant view among philosophers and scientists today. According to physicalism, a complete, purely physical description of reality leaves nothing out. But according to the hard problem of consciousness, any purely physical description of a conscious system such as the brain at least appears to leave something out: It could never fully capture what it is like to be that system. That is to say, it captures the objective but not the subjective aspects of consciousness: the brain function, but not our inner mental life.

In order to give both phenomena their proper due, a radical change of thinking is required.

Russell’s dual-aspect monism tries to fill in this deficiency. It accepts that the brain is a material system that behaves in accordance with the laws of physics. But it adds another, intrinsic aspect to matter which is hidden from the extrinsic, third-person perspective of physics and which therefore cannot be captured by any purely physical description. But although this intrinsic aspect eludes our physical theories, it does not elude our inner observations. Our own consciousness constitutes the intrinsic aspect of the brain, and this is our clue to the intrinsic aspect of other physical things. To paraphrase Arthur Schopenhauer’s succinct response to Kant: We can know the thing-in-itself because we are it.

Dual-aspect monism comes in moderate and radical forms. Moderate versions take the intrinsic aspect of matter to consist of so-called protoconscious or “neutral” properties: properties that are unknown to science, but also different from consciousness. The nature of such neither-mental-nor-physical properties seems quite mysterious. Like the aforementioned quantum theories of consciousness, moderate dual-aspect monism can therefore be accused of merely adding one mystery to another and expecting them to cancel out.

The most radical version of dual-aspect monism takes the intrinsic aspect of reality to consist of consciousness itself. This is decidedly not the same as subjective idealism, the view that the physical world is merely a structure within human consciousness, and that the external world is in some sense an illusion. According to dual-aspect monism, the external world exists entirely independently of human consciousness. But it would not exist independently of any kind of consciousness, because all physical things are associated with some form of consciousness of their own, as their own intrinsic realizer, or hardware.

Manuel Litran / Paris Match via Getty Images

As a solution to the hard problem of consciousness, dual-aspect monism faces objections of its own. The most common objection is that it results in panpsychism, the view that all things are associated with some form of consciousness. To critics, it’s just too implausible that fundamental particles are conscious. And indeed this idea takes some getting used to. But consider the alternatives. Dualism looks implausible on scientific grounds. Physicalism takes the objective, scientifically accessible aspect of reality to be the only reality, which arguably implies that the subjective aspect of consciousness is an illusion. Maybe so—but shouldn’t we be more confident that we are conscious, in the full subjective sense, than that particles are not?

A second important objection is the so-called combination problem. How and why does the complex, unified consciousness of our brains result from putting together particles with simple consciousness? This question looks suspiciously similar to the original hard problem. I and other defenders of panpsychism have argued that the combination problem is nevertheless not as hard as the original hard problem. In some ways, it is easier to see how to get one form of conscious matter (such as a conscious brain) from another form of conscious matter (such as a set of conscious particles) than how to get conscious matter from non-conscious matter. But many find this unconvincing. Perhaps it is just a matter of time, though. The original hard problem, in one form or another, has been pondered by philosophers for centuries. The combination problem has received much less attention, which gives more hope for a yet undiscovered solution.

The possibility that consciousness is the real concrete stuff of reality, the fundamental hardware that implements the software of our physical theories, is a radical idea. It completely inverts our ordinary picture of reality in a way that can be difficult to fully grasp. But it may solve two of the hardest problems in science and philosophy at once.

Hedda Hassel Mørch is a Norwegian philosopher and postdoctoral researcher hosted by the Center for Mind, Brain, and Consciousness at NYU. She works on the combination problem and other topics related to dual-aspect monism and panpsychism.

This article was originally published in our “Consciousness” issue in April 2017.