Sufism - A Strengthing Force in Pluralism

Sufism - A Strengthing Force in Pluralism

As Easter is a time of reflection for the two major monotheistic faiths i.e. Christianity and Judaism, I would like to share my thoughts on a facet of pluralism.

Mysticism or Sufism is the essence of all faiths. In this respect it can provide an enduring and meaningful bridge between various religious traditions that have evolved over different geographical, historical, liguistic and cultural contexts.The life and teachings of Mowlana Rumi are an expression of Sufism par excellence and indeed reflect this pluralism in the sense that they have a universal appeal and are not restricted to Islam. Therefore, they can contribute significantly to world peace especially in the Middle East where tensions are very often based on religious differences. The following anecdote which is taken from: "Say I am You, RUMI" by John Moyne and Coleman Barks underscores pluralism in the life of Rumi.

Aflaki describes Rumi's funeral in Konya: After they had brought the corpse on a wooden pallet, everyone uncovered their heads. Women, men, children, rich and poor. Men were walking and crying and tearing open their robes. Members of all communities were present. Christian, Jews, Greeks, Arabs, Turks, and representatives from each were walking in front holding their holy books and reading aloud, from the Psalms, the Gospels, the Quran, the Pentateuch. The wild tumult was heard by the sultan, who sent to ask why the members of other religions were so moved. They answered, "We saw in Rumi the real nature of Christ and Moses and all the prophets. Just as you claim that he was the Muhammad of our time, we found in him the Jesus and the Moses. Did he not say, 'We are like a flute, which with a single mode is tuned to two hundred religions.' Mevlana is the sun of truth which has shone on everyone." A Greek priest said, "Rumi is the bread which everyone needs to eat."

From the Marifati point of view (spiritual enlightenment through Sufism), all differences melt away. This is beautifully expressed by Hafiz as:

"I have learned so much from God that I can no longer call myself a Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Budhist , a Jew."

Mysticism or Sufism is the essence of all faiths. In this respect it can provide an enduring and meaningful bridge between various religious traditions that have evolved over different geographical, historical, liguistic and cultural contexts.The life and teachings of Mowlana Rumi are an expression of Sufism par excellence and indeed reflect this pluralism in the sense that they have a universal appeal and are not restricted to Islam. Therefore, they can contribute significantly to world peace especially in the Middle East where tensions are very often based on religious differences. The following anecdote which is taken from: "Say I am You, RUMI" by John Moyne and Coleman Barks underscores pluralism in the life of Rumi.

Aflaki describes Rumi's funeral in Konya: After they had brought the corpse on a wooden pallet, everyone uncovered their heads. Women, men, children, rich and poor. Men were walking and crying and tearing open their robes. Members of all communities were present. Christian, Jews, Greeks, Arabs, Turks, and representatives from each were walking in front holding their holy books and reading aloud, from the Psalms, the Gospels, the Quran, the Pentateuch. The wild tumult was heard by the sultan, who sent to ask why the members of other religions were so moved. They answered, "We saw in Rumi the real nature of Christ and Moses and all the prophets. Just as you claim that he was the Muhammad of our time, we found in him the Jesus and the Moses. Did he not say, 'We are like a flute, which with a single mode is tuned to two hundred religions.' Mevlana is the sun of truth which has shone on everyone." A Greek priest said, "Rumi is the bread which everyone needs to eat."

From the Marifati point of view (spiritual enlightenment through Sufism), all differences melt away. This is beautifully expressed by Hafiz as:

"I have learned so much from God that I can no longer call myself a Christian, a Hindu, a Muslim, a Budhist , a Jew."

Rapture in Missouri

The following anecdote about spiritual enlightenment of a Christian demonstrates the pluralism and universality of mystical experience - that these experiences are not confined to any sect or religion. This person had visions of Jesus, Muhammad and great sages of all traditions during the experience which confirms the essential unity at the mystical level.

Also he found out later through literature of another tradition the explanation of the experience in terms of the awakening of the kundalini which is the dormant or coiled energy at the base of the spine. Upon spiritual enlightenment, this energy is released and enraptures the entire body. Our Ginans also allude to this theory.

Rapture in Missouri

"When the fire came to my heart, the spiritual lightning struck. It was like being pierced in some unintelligible way."

By Bradford Keeney

Reprinted with permission from Bushman Shaman by Bradford Keeney, Destiny Books, copyright 2005.

It was a late afternoon in January 1971. I was casually walking along a sidewalk at the University of Missouri, where I was now enrolled.

It was an extraordinarily warm day for winter; the temperature had risen to the midseventies. People were wearing short-sleeved shirts during a time of year when shovels and plows typically were out clearing away snow and ice. I was headed for a record shop, probably humming a jazz tune, when out of the blue I felt the most intense comfort and joy I had ever known. Sheer calm, relaxation, and happiness spread through my whole being. As I went along the way, I began to feel my body getting lighter and lighter until I felt I had no weight at all. I wasn’t concerned; I assumed it was a consequence of feeling so good on a spectacular day. This bliss continued to escalate and elaborate. I soon found myself in the midst of a kind of awareness I had never known before. An uncannily deep calm and wide-ranging peacefulness flooded my consciousness and I felt a certainty about life that no words can adequately convey. In that moment it seemed that all questions about life’s meaning could be answered instantly and effortlessly. I felt complete peace and joy, but at the same time I did not feel in the least ego-centered. On the contrary, I was losing awareness of my individuality. I was floating in pure consciousness. This knowing did not reflect or analyze what was going on, nor did it show delight, amazement, curiosity, or celebration of the moment. It was more like a total centering of awareness and being that became compressed to a microscopic dot, pulling in the container that had once held it, setting it free of physical and conceptual weight and burden. Paradoxically, this getting smaller resulted in a feeling of also becoming larger, a state in which my sense of time and space was lost in a realization of eternal presence. As I write of this event now, it is obvious that I was having some kind of mystical experience. But at the time I experienced no outside evaluation of what was taking place. I was the experience, absent of all internal conversation.

My body moved without effort. It wouldn’t be totally inaccurate to say that I felt as though I were flying—or at least as though I were gliding along the sidewalk, without a single muscle exerting any force to move me. It was automatic movement of a body focused entirely on a sense of pure knowing that was absent of self. My body walked me up the steps of a small university chapel made of stone.

There was no one inside. The place was dark, with only a little light coming from a dimmed iron chandelier. A dozen wooden pews faced a Gothic-style altar. I walked up to the front pew, sat down, and felt like I had arrived at my natural place. I sat absolutely still, without thought or movement. In those moments I perceived what seemed to be the unity and wholeness of the cosmos.

I don’t know how long I sat there, but I do know that what I am going to describe lasted throughout the evening.

It began as a baptism into a river of absolute love. My deep sense of knowing melted into an even deeper awareness, both of being loved and of loving all of life. To be more accurate, I did not feel separate from the beloved, and the beloved was the world. As I plunged deeper and deeper into this infinite ocean of love, the inside of my body began to get heated. The base of my spine felt like an oven that was getting progressively warmer until it burned with red-hot coals. As the inner heat turned into what felt like molten lava, my body began to tremble.

It may seem strange to you that I had no fear or anxiety about what was happening. I believe this had to do with the fact that I was not in a dualistic relationship with the experience. There was no “I” having “the experience”—there was only unexamined experience. The former boundaries of my self had simultaneously shrunk to an unseen dot and expended to embrace the whole of the universe. As I went further into the depths of love’s unlimited oceanic space, I also went higher into the sky, feeling both the heavens above and the underbelly of Earth below.

The fireball within began to crawl slowly up my spine. It had a purpose of its own and nothing was going to stop it. Like a baby, after the breaking of its mother’s water, this birth was determinedly on its way. As the lavalike movement crept upward, heat spread throughout every cell in my body. I was on fire. My legs, abdomen, arms, and especially my hands felt as though they could melt through metal.

When the fire came to my heart, the spiritual lightning struck. It was like being pierced in some unintelligible way. My heart was opened and, rather than bursting, it grew and grew. The best way I can describe this is to say that both my heart and head felt as theough they physically expanded, first getting larger by a matter of inches, then by feet. Soon my body had no boundaries—my heart and my head had encompassed all of space and time. Now I was really shaking, trembling, vibrating, and sweating. The inner fire became even hotter, vaporizing the molten lava into pure energy as it entered my head. This steam went out of the top of my head and turned into a ball of light that then stretched itself to a kind of oval, egglike shape immediately in front of me.

My body didn’t cool down or become still. It continued to shake and boil as I beheld a sacred light that filled itself with the image of Jesus. I was in such an intense state of focus that it does not do justice to the experience to say that I saw Jesus. I saw, heard, and felt him at the same time. Every sensory process in my body was fully alive, creating a multidimensional, holistic encounter of the sacred.

As I beheld Jesus, as I felt him, a realization came that my hands were still hot as fire. I felt that I could anyone at that moment. Jesus then showed me other holders of sacred wisdom and light. His image dissolved into the image of the disciples, the Virgin Mary, and many other saints, some of whom I did not know. On and on, this slow-moving picture show continued, a magical multisensory film revealing what seemed to be the truths of all the world religions. I witnessed images of Gandhi, the Buddha, Mohammed, holy medicine people, shamans, yogis, mystics, and host of other sacred beings, all residing in immediate luminosity.

In this way I was shown that all religions and spiritual practices come from and return to the same source—a divine light born out of unlimited and unqualified love. This love boils inside the inner spiritual vessel and makes the body quake at the slightest awareness of its presence. As I received what others later told me was “direct transmission,” “satori,” “cosmic consciousness,” and “spiritual rapture,” my body dropped with sweat and was baptized with tears that would not stop flowing. I knew, without a doubt, that I was having the most important experience a human being could ever have. And I have never doubted since that time than an experience of that kind is the greatest gift a person can receive.

I believe now that I was hooked up to a cosmic source of timeless wisdom that was principally about relationship and econological connectedness (rather than particularlity and linear cause-and-effect interaction). In this hookup to a spiritual “gas station,” I was filled with some kind of spiritual energy and knowing. That night my spiritual insides were rewired. I was reborn and made into a completely different person. I felt as though I received my entire spiritual education that evening, although it is taking me the rest of my life to understand it. From that moment at 19 years of age, I have carried an inner spiritual heat that precipitates body shaking and trembling as soon as I focus on spiritual matters.

But on that evening, 33 years ago from the time I am writing this account, I didn’t know what to call what had happened. Nor did I know how to talk about it. I also wasn’t sure what to do with the experience. I did find that it took several weeks to cool myself down.

I went to the university bookstore in hope of finding a book tht would give me some clue about what had happened. As I walked along one section of the store, a book dropped off the shelf and landed at my feet. I saw that it was the autobiography of a man named Gopi Krishna. This was the first time I ever encountered the word kundalini. As I stood there reading Gopi Krishna’s account of how kundalini, the yoga term for inner spiritual energy, could be heated and activated, I was astonished to find that other people had had similar experiences to mine. However, in Gopi Krishna’s case the kundalini awakening was so strong that it hurt him. I was very lucky to have only felt pure love, bliss, and revelation. There was no pain or horror in my introduction to kundalini.

Later I learned that kundalini is the same as chi, ki, seiki, mana, wakan, jojo, voodoo, Manitou, yesod, baraka, Ruach, holy spirit and holy ghost power. Whatever name you give it, it is the same. Somehow we all carry this wound-up spring of life force within us, at the base of our spines, and it can be awakened, causing it to heat up and ascend the spinal column. As I learned more about what had happened to me I couldn’t help asking why kunalini had awakened in me. Was it an accident or had I done something to prepare myself for this?

I entered early adulthood with a secret understanding of my place in the world. I was here to help others be touched by spirit, whether directly or indirectly, however circumstances led that to happen. At the same time, I felt I wasn’t ready to reactivate the internal heat to the degree that it had already played itself out. I told nobody of my kundalini experience. Something inside me said it would take many years of preparation and training to be ready to return to that kind of experience again.

Also he found out later through literature of another tradition the explanation of the experience in terms of the awakening of the kundalini which is the dormant or coiled energy at the base of the spine. Upon spiritual enlightenment, this energy is released and enraptures the entire body. Our Ginans also allude to this theory.

Rapture in Missouri

"When the fire came to my heart, the spiritual lightning struck. It was like being pierced in some unintelligible way."

By Bradford Keeney

Reprinted with permission from Bushman Shaman by Bradford Keeney, Destiny Books, copyright 2005.

It was a late afternoon in January 1971. I was casually walking along a sidewalk at the University of Missouri, where I was now enrolled.

It was an extraordinarily warm day for winter; the temperature had risen to the midseventies. People were wearing short-sleeved shirts during a time of year when shovels and plows typically were out clearing away snow and ice. I was headed for a record shop, probably humming a jazz tune, when out of the blue I felt the most intense comfort and joy I had ever known. Sheer calm, relaxation, and happiness spread through my whole being. As I went along the way, I began to feel my body getting lighter and lighter until I felt I had no weight at all. I wasn’t concerned; I assumed it was a consequence of feeling so good on a spectacular day. This bliss continued to escalate and elaborate. I soon found myself in the midst of a kind of awareness I had never known before. An uncannily deep calm and wide-ranging peacefulness flooded my consciousness and I felt a certainty about life that no words can adequately convey. In that moment it seemed that all questions about life’s meaning could be answered instantly and effortlessly. I felt complete peace and joy, but at the same time I did not feel in the least ego-centered. On the contrary, I was losing awareness of my individuality. I was floating in pure consciousness. This knowing did not reflect or analyze what was going on, nor did it show delight, amazement, curiosity, or celebration of the moment. It was more like a total centering of awareness and being that became compressed to a microscopic dot, pulling in the container that had once held it, setting it free of physical and conceptual weight and burden. Paradoxically, this getting smaller resulted in a feeling of also becoming larger, a state in which my sense of time and space was lost in a realization of eternal presence. As I write of this event now, it is obvious that I was having some kind of mystical experience. But at the time I experienced no outside evaluation of what was taking place. I was the experience, absent of all internal conversation.

My body moved without effort. It wouldn’t be totally inaccurate to say that I felt as though I were flying—or at least as though I were gliding along the sidewalk, without a single muscle exerting any force to move me. It was automatic movement of a body focused entirely on a sense of pure knowing that was absent of self. My body walked me up the steps of a small university chapel made of stone.

There was no one inside. The place was dark, with only a little light coming from a dimmed iron chandelier. A dozen wooden pews faced a Gothic-style altar. I walked up to the front pew, sat down, and felt like I had arrived at my natural place. I sat absolutely still, without thought or movement. In those moments I perceived what seemed to be the unity and wholeness of the cosmos.

I don’t know how long I sat there, but I do know that what I am going to describe lasted throughout the evening.

It began as a baptism into a river of absolute love. My deep sense of knowing melted into an even deeper awareness, both of being loved and of loving all of life. To be more accurate, I did not feel separate from the beloved, and the beloved was the world. As I plunged deeper and deeper into this infinite ocean of love, the inside of my body began to get heated. The base of my spine felt like an oven that was getting progressively warmer until it burned with red-hot coals. As the inner heat turned into what felt like molten lava, my body began to tremble.

It may seem strange to you that I had no fear or anxiety about what was happening. I believe this had to do with the fact that I was not in a dualistic relationship with the experience. There was no “I” having “the experience”—there was only unexamined experience. The former boundaries of my self had simultaneously shrunk to an unseen dot and expended to embrace the whole of the universe. As I went further into the depths of love’s unlimited oceanic space, I also went higher into the sky, feeling both the heavens above and the underbelly of Earth below.

The fireball within began to crawl slowly up my spine. It had a purpose of its own and nothing was going to stop it. Like a baby, after the breaking of its mother’s water, this birth was determinedly on its way. As the lavalike movement crept upward, heat spread throughout every cell in my body. I was on fire. My legs, abdomen, arms, and especially my hands felt as though they could melt through metal.

When the fire came to my heart, the spiritual lightning struck. It was like being pierced in some unintelligible way. My heart was opened and, rather than bursting, it grew and grew. The best way I can describe this is to say that both my heart and head felt as theough they physically expanded, first getting larger by a matter of inches, then by feet. Soon my body had no boundaries—my heart and my head had encompassed all of space and time. Now I was really shaking, trembling, vibrating, and sweating. The inner fire became even hotter, vaporizing the molten lava into pure energy as it entered my head. This steam went out of the top of my head and turned into a ball of light that then stretched itself to a kind of oval, egglike shape immediately in front of me.

My body didn’t cool down or become still. It continued to shake and boil as I beheld a sacred light that filled itself with the image of Jesus. I was in such an intense state of focus that it does not do justice to the experience to say that I saw Jesus. I saw, heard, and felt him at the same time. Every sensory process in my body was fully alive, creating a multidimensional, holistic encounter of the sacred.

As I beheld Jesus, as I felt him, a realization came that my hands were still hot as fire. I felt that I could anyone at that moment. Jesus then showed me other holders of sacred wisdom and light. His image dissolved into the image of the disciples, the Virgin Mary, and many other saints, some of whom I did not know. On and on, this slow-moving picture show continued, a magical multisensory film revealing what seemed to be the truths of all the world religions. I witnessed images of Gandhi, the Buddha, Mohammed, holy medicine people, shamans, yogis, mystics, and host of other sacred beings, all residing in immediate luminosity.

In this way I was shown that all religions and spiritual practices come from and return to the same source—a divine light born out of unlimited and unqualified love. This love boils inside the inner spiritual vessel and makes the body quake at the slightest awareness of its presence. As I received what others later told me was “direct transmission,” “satori,” “cosmic consciousness,” and “spiritual rapture,” my body dropped with sweat and was baptized with tears that would not stop flowing. I knew, without a doubt, that I was having the most important experience a human being could ever have. And I have never doubted since that time than an experience of that kind is the greatest gift a person can receive.

I believe now that I was hooked up to a cosmic source of timeless wisdom that was principally about relationship and econological connectedness (rather than particularlity and linear cause-and-effect interaction). In this hookup to a spiritual “gas station,” I was filled with some kind of spiritual energy and knowing. That night my spiritual insides were rewired. I was reborn and made into a completely different person. I felt as though I received my entire spiritual education that evening, although it is taking me the rest of my life to understand it. From that moment at 19 years of age, I have carried an inner spiritual heat that precipitates body shaking and trembling as soon as I focus on spiritual matters.

But on that evening, 33 years ago from the time I am writing this account, I didn’t know what to call what had happened. Nor did I know how to talk about it. I also wasn’t sure what to do with the experience. I did find that it took several weeks to cool myself down.

I went to the university bookstore in hope of finding a book tht would give me some clue about what had happened. As I walked along one section of the store, a book dropped off the shelf and landed at my feet. I saw that it was the autobiography of a man named Gopi Krishna. This was the first time I ever encountered the word kundalini. As I stood there reading Gopi Krishna’s account of how kundalini, the yoga term for inner spiritual energy, could be heated and activated, I was astonished to find that other people had had similar experiences to mine. However, in Gopi Krishna’s case the kundalini awakening was so strong that it hurt him. I was very lucky to have only felt pure love, bliss, and revelation. There was no pain or horror in my introduction to kundalini.

Later I learned that kundalini is the same as chi, ki, seiki, mana, wakan, jojo, voodoo, Manitou, yesod, baraka, Ruach, holy spirit and holy ghost power. Whatever name you give it, it is the same. Somehow we all carry this wound-up spring of life force within us, at the base of our spines, and it can be awakened, causing it to heat up and ascend the spinal column. As I learned more about what had happened to me I couldn’t help asking why kunalini had awakened in me. Was it an accident or had I done something to prepare myself for this?

I entered early adulthood with a secret understanding of my place in the world. I was here to help others be touched by spirit, whether directly or indirectly, however circumstances led that to happen. At the same time, I felt I wasn’t ready to reactivate the internal heat to the degree that it had already played itself out. I told nobody of my kundalini experience. Something inside me said it would take many years of preparation and training to be ready to return to that kind of experience again.

It has often been said that Sufism is the backbone of all major revivals in Islamic history and that they can provide a bridge between conflicting interpretations and ideologies. The following is an article about Sufi activities in Iraq. They may have an important role to play if given proper recognition by the mainstream sects.

Iraq Sunnis, Shi'ites unite to mortify the flesh By

Andrew Hammond and Seif Fuad

Tue Aug 30, 8:09 AM ET

SULAIMANIYA, Iraq (Reuters) - Ahmed Jassem, a Shi'ite

from Iraq's holy city of Kerbala, sticks knives

into the bodies of his mostly Sunni followers. They

say they feel no pain, standing silently as the blades

pierce their skin.

ADVERTISEMENT

While sectarian strife threatens to tear Iraq apart,

mystical Sufi orders like the Kasnazani still manage

to bring Sunni and Shi'ite Muslims, as well as Arabs

and Kurds, together.

Sunni insurgents are fighting a relentless battle

against the Shi'ite-led government which came to power

after the U.S. invasion of 2003, but within the

confines of Sufi gatherings the Islamic sects mutilate

each other to get close to God.

"God said the most blessed among you is the most

pious, being close to God has nothing to do with your

background," said Jassem at a weekly meeting of the

Kasnazani order in Sulaimaniya in northern Iraq.

"The Kasnazani order makes no difference between Sunni

and Shi'ite, Arab and Kurd, or Iranian," said the man

whose job is to mortify the flesh of other Muslims.

His Sunni followers proudly display their wounds. One

man has three large kitchen knives lodged into his

scalp. Another has a skewer entering one cheek and

exiting from the other. All around people sway in a

hypnotic daze to the Sufi music.

SUFFERING TO GET CLOSER TO GOD

Sufism -- a mystical form of Islam that is more

liberal than the more demanding Sunni Wahhabism of

Saudi Arabia -- appeals to Shi'ites because of its

veneration of members of the Prophet Mohammad's

family.

The founders of many Sufi orders trace a bloodline

that goes back to the Prophet. Followers try to get

closer to the divine through dance, music and other

physical rituals.

The Kasnazani is Iraq's largest Sufi order and is a

branch of the Qadiriyya order which spreads across the

Islamic world.

"Body piercing with knives, skewers, drinking poison,

eating glass and taking electricity -- these are all

signs of being blessed by God," Jassem said, listing

Kasnazani practices.

"When the knife comes out, the dervish is healed

straight away. This is the blessing of God and power

of the order."

Each apprentice, or dervish, goes through spiritual

and physical training in order to learn how to endure

what would otherwise be considered forms of torture.

Qusay Abdel-Latif, a doctor from Basra in south Iraq,

said this divine intervention has tempered his belief

in science.

"Once they wrapped an electric wire around my body and

ran electricity through it, but I didn't feel

anything. I got closer to God through this," he said.

"I can only explain it through the divine power that

prevented the pain from the electricity, which as we

know should mean death or serious consequences," he

said.

LOW PROFILE

The Kasnazani order has been forced to take a low

profile in recent years. Its leader, Sheikh Mohammed

al-Kasnazani, left Baghdad for Iraqi Kurdistan in 1999

after Saddam Hussein's government became

suspicious of his popularity.

Kasnazani's sons are active in politics, running a

political party and a national newspaper which tries

to walk a fine line through the country's sectarian

minefield.

Islamist radicals among the insurgency frown on Sufism

as emotional superstition. While deadly attacks on the

order have been rare, 10 people died in a suicide

attack on a Kasnazani gathering in Balad, north of

Baghdad, in June.

"The Islamist extremists like al Qaeda, Ansar al-Sunna

and the Wahhabis are against Sufism, and since

Kasnazani is the main order they are against us," said

Abdel-Salam al-Hadithi, spokesman of the Central

Council for Sufi Orders in Baghdad.

The Kasnazani order has been forced to scale down its

activities in Sunni-dominated west Iraq, Hadithi said.

In normal times, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis would

head to celebrations of holy figures but now people

are no longer going, fearing random violence or

deliberate attacks.

"Iraq is sinking in a sea of blood right now and no

one is safe, whatever their sect or ethnic

background," Hadithi said.

Iraq Sunnis, Shi'ites unite to mortify the flesh By

Andrew Hammond and Seif Fuad

Tue Aug 30, 8:09 AM ET

SULAIMANIYA, Iraq (Reuters) - Ahmed Jassem, a Shi'ite

from Iraq's holy city of Kerbala, sticks knives

into the bodies of his mostly Sunni followers. They

say they feel no pain, standing silently as the blades

pierce their skin.

ADVERTISEMENT

While sectarian strife threatens to tear Iraq apart,

mystical Sufi orders like the Kasnazani still manage

to bring Sunni and Shi'ite Muslims, as well as Arabs

and Kurds, together.

Sunni insurgents are fighting a relentless battle

against the Shi'ite-led government which came to power

after the U.S. invasion of 2003, but within the

confines of Sufi gatherings the Islamic sects mutilate

each other to get close to God.

"God said the most blessed among you is the most

pious, being close to God has nothing to do with your

background," said Jassem at a weekly meeting of the

Kasnazani order in Sulaimaniya in northern Iraq.

"The Kasnazani order makes no difference between Sunni

and Shi'ite, Arab and Kurd, or Iranian," said the man

whose job is to mortify the flesh of other Muslims.

His Sunni followers proudly display their wounds. One

man has three large kitchen knives lodged into his

scalp. Another has a skewer entering one cheek and

exiting from the other. All around people sway in a

hypnotic daze to the Sufi music.

SUFFERING TO GET CLOSER TO GOD

Sufism -- a mystical form of Islam that is more

liberal than the more demanding Sunni Wahhabism of

Saudi Arabia -- appeals to Shi'ites because of its

veneration of members of the Prophet Mohammad's

family.

The founders of many Sufi orders trace a bloodline

that goes back to the Prophet. Followers try to get

closer to the divine through dance, music and other

physical rituals.

The Kasnazani is Iraq's largest Sufi order and is a

branch of the Qadiriyya order which spreads across the

Islamic world.

"Body piercing with knives, skewers, drinking poison,

eating glass and taking electricity -- these are all

signs of being blessed by God," Jassem said, listing

Kasnazani practices.

"When the knife comes out, the dervish is healed

straight away. This is the blessing of God and power

of the order."

Each apprentice, or dervish, goes through spiritual

and physical training in order to learn how to endure

what would otherwise be considered forms of torture.

Qusay Abdel-Latif, a doctor from Basra in south Iraq,

said this divine intervention has tempered his belief

in science.

"Once they wrapped an electric wire around my body and

ran electricity through it, but I didn't feel

anything. I got closer to God through this," he said.

"I can only explain it through the divine power that

prevented the pain from the electricity, which as we

know should mean death or serious consequences," he

said.

LOW PROFILE

The Kasnazani order has been forced to take a low

profile in recent years. Its leader, Sheikh Mohammed

al-Kasnazani, left Baghdad for Iraqi Kurdistan in 1999

after Saddam Hussein's government became

suspicious of his popularity.

Kasnazani's sons are active in politics, running a

political party and a national newspaper which tries

to walk a fine line through the country's sectarian

minefield.

Islamist radicals among the insurgency frown on Sufism

as emotional superstition. While deadly attacks on the

order have been rare, 10 people died in a suicide

attack on a Kasnazani gathering in Balad, north of

Baghdad, in June.

"The Islamist extremists like al Qaeda, Ansar al-Sunna

and the Wahhabis are against Sufism, and since

Kasnazani is the main order they are against us," said

Abdel-Salam al-Hadithi, spokesman of the Central

Council for Sufi Orders in Baghdad.

The Kasnazani order has been forced to scale down its

activities in Sunni-dominated west Iraq, Hadithi said.

In normal times, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis would

head to celebrations of holy figures but now people

are no longer going, fearing random violence or

deliberate attacks.

"Iraq is sinking in a sea of blood right now and no

one is safe, whatever their sect or ethnic

background," Hadithi said.

Don't you see that the roads to Makkah are all different?...The roads are different, the goal one...When people come there, all quarrels or differences or disputes that happened along the road are resolved...Those who shouted at each other along the road 'you are wrong' or 'you are an infidel' forgot their differences when they come there because there, all hearts are in unison. - Rumi

The following poem is an expression of the highest consciousness attained through spiritual elvation where all physical identities and barriers be they religious, cultural, national, tribal are broken apart and transended into the only one.

Rumi - I Am The Life Of My Beloved:

What can I do, Muslims? I do not know myself.

I am no Christian, no Jew, no Magian, no Musulman.

Not of the East, not of the West. Not of the land, not of the sea.

Not of the Mine of Nature, not of the circling heavens,

Not of earth, not of water, not of air, not of fire;

Not of the throne, not of the ground, of existence, of being;

Not of India, China, Bulgaria, Saqseen;

Not of the kingdom of the Iraqs, or of Khorasan;

Not of this world or the next: of heaven or hell;

Not of Adam, Eve, the gardens of Paradise or Eden;

My place placeless, my trace traceless.

Neither body nor soul: all is the life of my Beloved.

I have put away duality: I have seen the Two worlds as one.

I desire One, I know One, I see One, I call One.

---Jalaluddin Rumi---

Rumi - I Am The Life Of My Beloved:

What can I do, Muslims? I do not know myself.

I am no Christian, no Jew, no Magian, no Musulman.

Not of the East, not of the West. Not of the land, not of the sea.

Not of the Mine of Nature, not of the circling heavens,

Not of earth, not of water, not of air, not of fire;

Not of the throne, not of the ground, of existence, of being;

Not of India, China, Bulgaria, Saqseen;

Not of the kingdom of the Iraqs, or of Khorasan;

Not of this world or the next: of heaven or hell;

Not of Adam, Eve, the gardens of Paradise or Eden;

My place placeless, my trace traceless.

Neither body nor soul: all is the life of my Beloved.

I have put away duality: I have seen the Two worlds as one.

I desire One, I know One, I see One, I call One.

---Jalaluddin Rumi---

Government to set up Sufi Advisory Council

By Ahmad Hassan

Sunday, 07 Jun, 2009 | 10:25 PM PST |

ISLAMABAD: The government on Sunday announced setting up of a 7-member ‘Sufi Advisory Council’ (SAC) with an aim to combating extremism and fanaticism by spreading Sufism in the country.

Interestingly, the SAC replaces an earlier such exercise when the PML-Q government had notified constitution of a ‘National Sufi Council’ with party president Chaudhry Shujaat as its president and taking some progressive intellectuals on it to give Sufism a chance to flourish.

The said NSC however became dormant after holding a ‘Sufi gala’ — a semi-music festival — in Lahore’s Qala and printing calendars in the name of council.

According to an official handout Haji Muhammad Tayyab who heads one of several factions of Jamiat Ulema Pakistan (JUP) will be the chairman of the SAC which will be holding its first meeting at the ministry of religious affairs on Tuesday June 9.

Other members of the SAC include Sahibzada Sajidur Rahman, Maulana Syed Charaghuddin Shah, Rawalpindi, Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi Islamabad, Hafiz Muhammad Tufail Islamabad, Iranmullah Jan, Director General Ministry of Religious Affairs and Abdul Ahad Haqqani Deputy Director R&S) MORA.

While two last named persons were ministry’s officials Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi is a retired government official, Sajidur Rahman is a close relative of Raja Zafarul Haq (PML-N) and Charaghuddin Shah is a member of PML-Q’s Ulema Mashaikh wing.

Haji Hanif Tayyab remained part of former military dictator Ziaul Haq’s regime in various capacities including a minister.

It is not clear whether another religious body could be set up in presence of Council of Islamic Ideology which is a constitutional body.

http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/daw ... ncil-zj-08

By Ahmad Hassan

Sunday, 07 Jun, 2009 | 10:25 PM PST |

ISLAMABAD: The government on Sunday announced setting up of a 7-member ‘Sufi Advisory Council’ (SAC) with an aim to combating extremism and fanaticism by spreading Sufism in the country.

Interestingly, the SAC replaces an earlier such exercise when the PML-Q government had notified constitution of a ‘National Sufi Council’ with party president Chaudhry Shujaat as its president and taking some progressive intellectuals on it to give Sufism a chance to flourish.

The said NSC however became dormant after holding a ‘Sufi gala’ — a semi-music festival — in Lahore’s Qala and printing calendars in the name of council.

According to an official handout Haji Muhammad Tayyab who heads one of several factions of Jamiat Ulema Pakistan (JUP) will be the chairman of the SAC which will be holding its first meeting at the ministry of religious affairs on Tuesday June 9.

Other members of the SAC include Sahibzada Sajidur Rahman, Maulana Syed Charaghuddin Shah, Rawalpindi, Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi Islamabad, Hafiz Muhammad Tufail Islamabad, Iranmullah Jan, Director General Ministry of Religious Affairs and Abdul Ahad Haqqani Deputy Director R&S) MORA.

While two last named persons were ministry’s officials Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi is a retired government official, Sajidur Rahman is a close relative of Raja Zafarul Haq (PML-N) and Charaghuddin Shah is a member of PML-Q’s Ulema Mashaikh wing.

Haji Hanif Tayyab remained part of former military dictator Ziaul Haq’s regime in various capacities including a minister.

It is not clear whether another religious body could be set up in presence of Council of Islamic Ideology which is a constitutional body.

http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/daw ... ncil-zj-08

Omid Safi speaks on `The ethics of reform'

July 2009

Professor Omid Safi of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, delivered the third lecture in the `Talking Ethics' series at the IIS on 19 June 2009. What the Sufi tradition brings to the practice of Muslim ethics, Professor Safi argued, is a deep appreciation of the lived nature of what the Holy Qur'an and the Prophet taught.

Social justice as a defining value in the founding age of Islam and Muslim ethics has remained vital to Sufi networks, where it provides rich bonds of solidarity. Indeed, the Holy Qur'an celebrates justice (`adl) with beauty (ihsan) – which inspires the understanding of solidarity among Sufis as one of both love and social bonding. This was interwoven with values of nonviolence and the instance on seeing each individual as belonging to the realm of the sacred.

Amidst the emphasis in modernity on citizens being `children of the now', engaged fully with contemporary public issues, Professor Safi saw in tradition a redeeming power that Muslim scholars would do well to keep in perspective. There was far too much debate about what `Islam' is not, and all the more so since the events of 11 September, 2001; yet one only affiliated with a religion for what it actually was, rather than what it was not. Here, the Sufi tradition offered a living link to the values that Islam had always espoused. Professor Safi spoke of those values as `Muhammadi ethics', a fusion of the spiritual and social that the Holy Qur'an repeatedly addressed and which Prophet Muhammad lived. At the same time, Professor Safi noted that tradition itself must be understood as dynamic – one that had to be lived and validated from day to day – not a passive heritage.

Questions from the audience focused chiefly on how such an ethics could survive and prevail in a world that was often highly uncivil. This was also raised earlier in the introductory remarks by Dr Amyn Sajoo, the organiser of this series, who recalled that `moral engagement' ran all kinds of risks from various parts of the public square. Professor Safi agreed that there were practical limits to a Sufi-centred strategy alone – but observed that those advocating reform (islah) were obliged to hold fast to the values of equity, solidarity and love that Islam stood for. This was also the message of the iconic figure of Mowlana Rumi (d.1273), who spent a lifetime in maturing the spiritual instincts and ethics for which he is celebrated across the world.

Dr Amyn Sajoo: Introductory Remarks

Abstract of the lecture: "The Ethics of Reform: Justice and Love in Contemporary Islam"

http://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=110422

July 2009

Professor Omid Safi of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, delivered the third lecture in the `Talking Ethics' series at the IIS on 19 June 2009. What the Sufi tradition brings to the practice of Muslim ethics, Professor Safi argued, is a deep appreciation of the lived nature of what the Holy Qur'an and the Prophet taught.

Social justice as a defining value in the founding age of Islam and Muslim ethics has remained vital to Sufi networks, where it provides rich bonds of solidarity. Indeed, the Holy Qur'an celebrates justice (`adl) with beauty (ihsan) – which inspires the understanding of solidarity among Sufis as one of both love and social bonding. This was interwoven with values of nonviolence and the instance on seeing each individual as belonging to the realm of the sacred.

Amidst the emphasis in modernity on citizens being `children of the now', engaged fully with contemporary public issues, Professor Safi saw in tradition a redeeming power that Muslim scholars would do well to keep in perspective. There was far too much debate about what `Islam' is not, and all the more so since the events of 11 September, 2001; yet one only affiliated with a religion for what it actually was, rather than what it was not. Here, the Sufi tradition offered a living link to the values that Islam had always espoused. Professor Safi spoke of those values as `Muhammadi ethics', a fusion of the spiritual and social that the Holy Qur'an repeatedly addressed and which Prophet Muhammad lived. At the same time, Professor Safi noted that tradition itself must be understood as dynamic – one that had to be lived and validated from day to day – not a passive heritage.

Questions from the audience focused chiefly on how such an ethics could survive and prevail in a world that was often highly uncivil. This was also raised earlier in the introductory remarks by Dr Amyn Sajoo, the organiser of this series, who recalled that `moral engagement' ran all kinds of risks from various parts of the public square. Professor Safi agreed that there were practical limits to a Sufi-centred strategy alone – but observed that those advocating reform (islah) were obliged to hold fast to the values of equity, solidarity and love that Islam stood for. This was also the message of the iconic figure of Mowlana Rumi (d.1273), who spent a lifetime in maturing the spiritual instincts and ethics for which he is celebrated across the world.

Dr Amyn Sajoo: Introductory Remarks

Abstract of the lecture: "The Ethics of Reform: Justice and Love in Contemporary Islam"

http://www.iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=110422

Sufism: Faith's smiling face

By Ali Eteraz

author

Were Islam a buffet, I'd be the guy that shows up in the morning and stays late, picking and tasting every item, simultaneously stuffed and starving, simultaneously gluttonous and bulimic. From madrassas in rural Pakistan to traditional elders in the country's urban bungalows; from cramped immigrant mosques in Brooklyn to the technocratic Islam at elite East Coast universities; from someone veiling his spiritual malaise with romanticized visions of Islamic supremacism to someone who douses his hypocrisies in liberal Islamic reform -- I have, to put it mildly, lived a lot of Islams. I am done with dabbling now; or maybe I am just taking a break; either way, it has allowed me to tell some fun stories about the religion. One of those that I did not get an opportunity to relate in my book is about my experiences with the sorts of Sufis that I've come across in America.

Sufism, generally referred to as the mystical or "inner" dimension of Islam, which tends to put a focus on one's individual relation to God through guidance from a spiritual elder, has been around almost since the beginning of the religion. It is worldwide. During the course of the 20th Century, Sufism made its way to America. Now it exists in orthodox and heterodox ways, in "drunk" and "sober" ways, in universalist and exclusivist ways, and even in the form of a female whirling dervish that dances to Turkish electronica.

There is, for example, a Sufi mosque with a glittering white dome located just outside of Philadelphia, affiliated with a Sufi order named after Bawa Muhaiyaddeen. He came this country in the 1970's after decades of mystical leadership in Sri Lanka. His work of simple living is now carried out by his followers. It is said that the writer, Coleman Barks, who is famous for his translations of the mystic, Rumi, began his project when Bawa Muhaiyaddeen appeared to him in a dream. When I lived in Philly I went to this mosque a few times. Once it was to serve as an extra in an experimental silent film by a student director. She needed to film inside a Muslim prayer area with a lot of equipment and was afraid of asking the more orthodox mosques in case they didn't approve of her storyline or all the non-Muslims she was bringing along.

Another Sufi landmark is in Manhattan, just next to White Horse Tavern, the pub where Dylan Thomas drank. The mosque, which houses the American followers of a Persian order, is located inside a small brown building with a calligraphic sign. When I was deeply unhappy practicing law I went to one of the gatherings here and sat around in the sitting area, eventually having a long heart-to-heart with the rector of the place. A number of people of various ethnicities -- both men and women -- came inside during that time and went to an inner room where they engaged in their spiritual practices. I wanted to join them but was told that before I could I would have to have a meeting with the order's spiritual leader, who was not in New York at the time.

I also went to a gathering of a conservative Sufi order called the Naqshbandi. They met on Friday nights in an old apartment building near Lincoln Tunnel. Men and women were both present but sat on opposite sides of the room. The men wore green turbans and the women covered their hair. There was an older saint with a long beard who sat in the middle and once the lights were dimmed, led a series of prayers recited in a rhythmic way. I had gone in just to observe but by the end I was swaying my head and participating. The guy that had invited me was someone I used to have a lot of religious arguments with. Afterwards we became friendly.

Going around the country I have met all sorts of American Sufis. When I was in college a former hippie once came to lecture some of us and talked about the purification of the heart and how to avoid all the "new-age" Sufis. I also maintain correspondence with a Sufi from the Shia tradition. He is unique because unlike most of the placid and restrained mystics I've met, he tends to lose his temper very quickly. I have almost met a number of individuals that have made a close study of Ibn Arabi, a Spanish mystic whose ideas about the unity of creation evoke Neruda and Whitman.

To me, the most interesting thing about Sufism is its paradoxical place in my life. Somehow, for all of my stuttering, stammering, rationalizing, sometimes authentic, mostly sinful, always perplexed approach to faith, it has been these austere Sufis, with their stentorian obeisance to a higher principle, their complete surrender to the authority of a saintly figure, their often pre-modern outlook, who have been most inclined to embrace me without asking questions. They retain a view towards chaos of the world that is not merely hopeful, but outright cheerful, a smile stretched eternally onto the face of the faith. For all of us melancholics and obsessives and loners and miscreants, with our spiritual gastroenteritis and Nietzschean dyspepsia, the existence of the Sufis is thoroughly soothing, even if we never join their orders or learn their prayers.

As for the electronica loving whirling dervish, I am still trying to meet her.

Ali Eteraz, author of "Children of Dust: A Memoir of Pakistan", was born in Pakistan and has lived in the Middle East, the Caribbean, and the United States. A graduate of Emory University and Temple Law School, he was selected for the Outstanding Scholar's Program at the United States Department of Justice and later worked in corporate litigation in Manhattan. His blog in the Islamosphere received nearly two million views as well as a Brass Crescent award for originality.

http://newsweek.washingtonpost.com/onfa ... _face.html

By Ali Eteraz

author

Were Islam a buffet, I'd be the guy that shows up in the morning and stays late, picking and tasting every item, simultaneously stuffed and starving, simultaneously gluttonous and bulimic. From madrassas in rural Pakistan to traditional elders in the country's urban bungalows; from cramped immigrant mosques in Brooklyn to the technocratic Islam at elite East Coast universities; from someone veiling his spiritual malaise with romanticized visions of Islamic supremacism to someone who douses his hypocrisies in liberal Islamic reform -- I have, to put it mildly, lived a lot of Islams. I am done with dabbling now; or maybe I am just taking a break; either way, it has allowed me to tell some fun stories about the religion. One of those that I did not get an opportunity to relate in my book is about my experiences with the sorts of Sufis that I've come across in America.

Sufism, generally referred to as the mystical or "inner" dimension of Islam, which tends to put a focus on one's individual relation to God through guidance from a spiritual elder, has been around almost since the beginning of the religion. It is worldwide. During the course of the 20th Century, Sufism made its way to America. Now it exists in orthodox and heterodox ways, in "drunk" and "sober" ways, in universalist and exclusivist ways, and even in the form of a female whirling dervish that dances to Turkish electronica.

There is, for example, a Sufi mosque with a glittering white dome located just outside of Philadelphia, affiliated with a Sufi order named after Bawa Muhaiyaddeen. He came this country in the 1970's after decades of mystical leadership in Sri Lanka. His work of simple living is now carried out by his followers. It is said that the writer, Coleman Barks, who is famous for his translations of the mystic, Rumi, began his project when Bawa Muhaiyaddeen appeared to him in a dream. When I lived in Philly I went to this mosque a few times. Once it was to serve as an extra in an experimental silent film by a student director. She needed to film inside a Muslim prayer area with a lot of equipment and was afraid of asking the more orthodox mosques in case they didn't approve of her storyline or all the non-Muslims she was bringing along.

Another Sufi landmark is in Manhattan, just next to White Horse Tavern, the pub where Dylan Thomas drank. The mosque, which houses the American followers of a Persian order, is located inside a small brown building with a calligraphic sign. When I was deeply unhappy practicing law I went to one of the gatherings here and sat around in the sitting area, eventually having a long heart-to-heart with the rector of the place. A number of people of various ethnicities -- both men and women -- came inside during that time and went to an inner room where they engaged in their spiritual practices. I wanted to join them but was told that before I could I would have to have a meeting with the order's spiritual leader, who was not in New York at the time.

I also went to a gathering of a conservative Sufi order called the Naqshbandi. They met on Friday nights in an old apartment building near Lincoln Tunnel. Men and women were both present but sat on opposite sides of the room. The men wore green turbans and the women covered their hair. There was an older saint with a long beard who sat in the middle and once the lights were dimmed, led a series of prayers recited in a rhythmic way. I had gone in just to observe but by the end I was swaying my head and participating. The guy that had invited me was someone I used to have a lot of religious arguments with. Afterwards we became friendly.

Going around the country I have met all sorts of American Sufis. When I was in college a former hippie once came to lecture some of us and talked about the purification of the heart and how to avoid all the "new-age" Sufis. I also maintain correspondence with a Sufi from the Shia tradition. He is unique because unlike most of the placid and restrained mystics I've met, he tends to lose his temper very quickly. I have almost met a number of individuals that have made a close study of Ibn Arabi, a Spanish mystic whose ideas about the unity of creation evoke Neruda and Whitman.

To me, the most interesting thing about Sufism is its paradoxical place in my life. Somehow, for all of my stuttering, stammering, rationalizing, sometimes authentic, mostly sinful, always perplexed approach to faith, it has been these austere Sufis, with their stentorian obeisance to a higher principle, their complete surrender to the authority of a saintly figure, their often pre-modern outlook, who have been most inclined to embrace me without asking questions. They retain a view towards chaos of the world that is not merely hopeful, but outright cheerful, a smile stretched eternally onto the face of the faith. For all of us melancholics and obsessives and loners and miscreants, with our spiritual gastroenteritis and Nietzschean dyspepsia, the existence of the Sufis is thoroughly soothing, even if we never join their orders or learn their prayers.

As for the electronica loving whirling dervish, I am still trying to meet her.

Ali Eteraz, author of "Children of Dust: A Memoir of Pakistan", was born in Pakistan and has lived in the Middle East, the Caribbean, and the United States. A graduate of Emory University and Temple Law School, he was selected for the Outstanding Scholar's Program at the United States Department of Justice and later worked in corporate litigation in Manhattan. His blog in the Islamosphere received nearly two million views as well as a Brass Crescent award for originality.

http://newsweek.washingtonpost.com/onfa ... _face.html

Sufi Soul, The Mystic Music of Islam

A documentary film by Simon Broughton and William Dalrymple. Post-discussion led by Dr. Hussein Rashid.

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 11

Time: 7:00pm - 9:00pm

Cost: Free; reservations required.

The mystical sounds of Islam communicating messages of peace, tolerance and love are reverently captured in the documentary film Sufi Soul by Simon Broughton and William Dalrymple. Sufis believe that it is possible to embrace the Divine Presence through individual restoration. For Sufi followers, music is a way of getting closer to God. This film traces the shared roots of Christianity and Islam in the Middle East and discovers Sufism to be a peaceful and pluralistic bastion with a worldwide following. It features many acclaimed performers, including Abida Parveen and Youssou N’Dour as well as Sain Zahoor, The Galata Mevlevi Ensemble, Kudsi Erguner, Mercan Dede, Goonga and Mithu Sain, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and Abdennbi Zizi. Filmmaker Simon Broughton is editor of the world music magazine Songlines – a leader in its field. William Dalrymple is a historian, writer, broadcaster, and founder of Asia’s largest literary festival.

Dr. Hussein Rashid will lead a post-discussion of Sufi musical history, providing a new avenue for the public to appreciate and understand the history of the mystic music of Islam. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University and is a passionate instructor at one of the largest interfaith centers in Manhattan.

Presented and sponsored by the Aga Khan Council for the Western United States and the Skirball Cultural Center. The Aga Khan, Imam (spiritual leader) of Shia Ismaili Muslims, urges that the “clash of ignorance” between non-Muslims and Muslims be addressed through education and exposure. This film is an example of such shared learning.

http://www.festivalofsacredmusic.org/ev ... usic-islam

A documentary film by Simon Broughton and William Dalrymple. Post-discussion led by Dr. Hussein Rashid.

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 11

Time: 7:00pm - 9:00pm

Cost: Free; reservations required.

The mystical sounds of Islam communicating messages of peace, tolerance and love are reverently captured in the documentary film Sufi Soul by Simon Broughton and William Dalrymple. Sufis believe that it is possible to embrace the Divine Presence through individual restoration. For Sufi followers, music is a way of getting closer to God. This film traces the shared roots of Christianity and Islam in the Middle East and discovers Sufism to be a peaceful and pluralistic bastion with a worldwide following. It features many acclaimed performers, including Abida Parveen and Youssou N’Dour as well as Sain Zahoor, The Galata Mevlevi Ensemble, Kudsi Erguner, Mercan Dede, Goonga and Mithu Sain, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan and Abdennbi Zizi. Filmmaker Simon Broughton is editor of the world music magazine Songlines – a leader in its field. William Dalrymple is a historian, writer, broadcaster, and founder of Asia’s largest literary festival.

Dr. Hussein Rashid will lead a post-discussion of Sufi musical history, providing a new avenue for the public to appreciate and understand the history of the mystic music of Islam. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University and is a passionate instructor at one of the largest interfaith centers in Manhattan.

Presented and sponsored by the Aga Khan Council for the Western United States and the Skirball Cultural Center. The Aga Khan, Imam (spiritual leader) of Shia Ismaili Muslims, urges that the “clash of ignorance” between non-Muslims and Muslims be addressed through education and exposure. This film is an example of such shared learning.

http://www.festivalofsacredmusic.org/ev ... usic-islam

]The Sufi Spirit

Prayer that brings a permanent awareness of the Divine Reality is the aim of Sufism first and foremost, which London based Sufi scholar, Reza Shah-Kazemi, believes is the key to its universality. Sufism's mystical universalism is what interests Hebrew University scholar, Sara Sviri, who reveals the fascinating phenomenon of 'Jewish Sufism'.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/pro ... it/3686180

Prayer that brings a permanent awareness of the Divine Reality is the aim of Sufism first and foremost, which London based Sufi scholar, Reza Shah-Kazemi, believes is the key to its universality. Sufism's mystical universalism is what interests Hebrew University scholar, Sara Sviri, who reveals the fascinating phenomenon of 'Jewish Sufism'.

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/pro ... it/3686180

One and Many: The pluralistic expressions In Sufi poetry

By: Raheel Lakhani, Uploaded: 11th June 2012

http://blogs.aaj.tv/2012/06/one-and-man ... fi-poetry/

By: Raheel Lakhani, Uploaded: 11th June 2012

http://blogs.aaj.tv/2012/06/one-and-man ... fi-poetry/

Sufism aims the individual to a spiritual awakening through prayer and devotion

The term sufi, from the Arabic suf is thought to have been derived in the eight century to refer to those who wore coarse woollen garments. Gradually it came to be designated to a group of those who differentiated themselves by stressing certain teachings of the Qur’an and the sunnah. By the ninth century, the term tasawwuff (literally “being a Sufi”) was adopted by some representatives of this group as a designation of their beliefs and practices.

Sufism developed as a reaction against the worldliness of the early Umayyad period (661-749), stressing contemplation and spiritual development. Sufism aimed the individual to gain a deep knowledge of God’s will, therefore, seekers had to embrace a path of devotion and prayer that would lead to a spiritual awakening. Thus, the sharia has a counterpart, the tariqa (‘way’), the journey and discipline undertaken by the Sufi in the quest for the knowledge of God.

Beggar’s bowl (kashkul), dated 18th century Iran, carried by a Sufi dervish as a sign of renouncing all worldly possessions. The upper band of inscription contains the Nad-e ‘Ali, the devotional prayer to ‘Ali. (Image: Aga Khan Museum)

In the early stages, Sufism developed into a system of mystical orders, named after their founding teachers, but tracing their spiritual genealogy to the teachings of Prophet Muhammad and Ali Ibn Abi Talib, who they considered to have been endowed with the special mission of explaining the esoteric teachings of the Qur’an. Sufi masters were known as pirs or murshids, while the followers were known as murids, and were bound to the murshid by the baya, oath of allegiance.

Access to the normative, textual Islam based on the Qur’an, hadith, fiqh (jurisprudence), tafsir (hermeneutics) required the knowledge of Arabic, restricting its appeal. The Sufi masters were able to convey Islamic teachings in local languages. The Sufi dhikrs, ceremonies in remembrance of God derived from the Qurʾānic injunction “And remember God often” (sura 62, verse 10), developed spiritual techniques that meshed with practices from local traditions such as ritual dances and controlled yoga-style breathing.

Sufism was influential in spreading Islam to sub-Saharan and West Africa in the ninth to eleventh centuries, where they spread along trade routes. Organized Sufism, however, was consolidated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, gaining ground rapidly in Asia in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions. Sufism was taken to China in the seventeenth century by Ma Laichi and other Sufis who had studied in Mecca and were influenced by the descendants of the Sufi master Afaq Khoja (1626-1694), a religious and political leader in Kashgaria (present day southern Xinjiang, China).

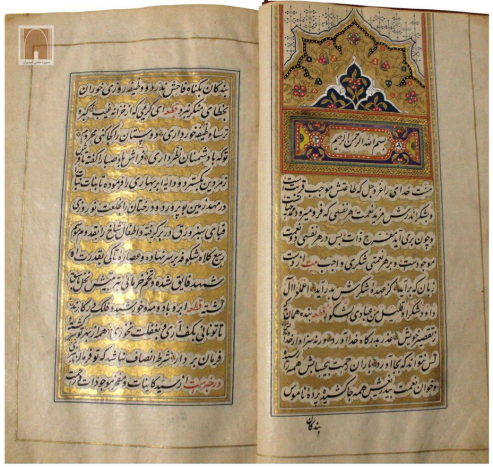

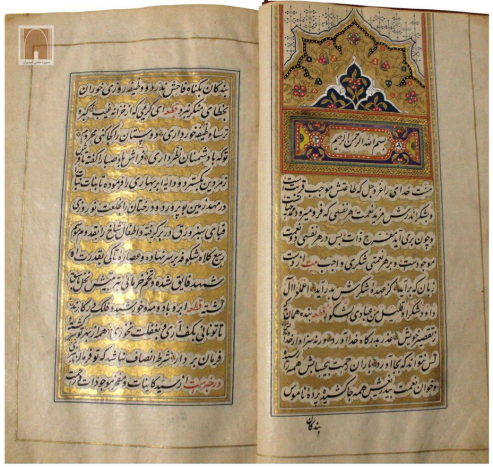

Manuscript of the Mathnavi of Rumi, dated 1602 Iran (Aga Khan Museum)

The mystic writings of the Persian poet Jalāl al-Dīn al-Rūmī (1207–73), also called by the honorific title Mawlānā are generally considered to be the supreme expression of Sufism. After his death, his disciples were organized as the Mawlawīyah (or Mehlevi) order, commonly known as the Whirling Dervishes due to their practice of whirling while performing the dhikr.

The Persian poet Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār Attar, who authored the finest spiritual parable in the Persian language, The Concourse of the Birds, was one of the greatest Sufi writers and thinkers, composing many brilliant prose works.

Nizari Ismailism and Persian Sufism developed a close relationship after the fall of the state of Alamut in 1256. For the first two centuries after the fall, the Imams remained inaccessible to the community in order to avoid persecution. The community concealed their identity under the mantle of Sufism without establishing formal affiliations with any particular Sufi tariqas that were spreading in Persia and Central Asia. At the same time, Sufis employed the batini tawil or esoteric teachings more widely ascribed to the Ismailis. The Nizari Ismaili Imams, who were still obliged to hide their identities, appeared to outsiders as murshids, often adopting Sufi names such as Shah Qalandar adopted by Imam Mustansir bi’llah II (d. 1480).

Sources:

Malise Ruthven, Azim Nanji, Sufi Orders 1100-1900, Historical Atlas of the Islamic World, Cartographica Limited 2004

Azim Nanji, Dictionary of Islam, Penguin Books, 2008

Sufism, Encyclopaedia Britannica (Accessed October 2015)

Compiled by Nimira Dewji

https://ismailimail.wordpress.com/2015/ ... -devotion/

The term sufi, from the Arabic suf is thought to have been derived in the eight century to refer to those who wore coarse woollen garments. Gradually it came to be designated to a group of those who differentiated themselves by stressing certain teachings of the Qur’an and the sunnah. By the ninth century, the term tasawwuff (literally “being a Sufi”) was adopted by some representatives of this group as a designation of their beliefs and practices.

Sufism developed as a reaction against the worldliness of the early Umayyad period (661-749), stressing contemplation and spiritual development. Sufism aimed the individual to gain a deep knowledge of God’s will, therefore, seekers had to embrace a path of devotion and prayer that would lead to a spiritual awakening. Thus, the sharia has a counterpart, the tariqa (‘way’), the journey and discipline undertaken by the Sufi in the quest for the knowledge of God.

Beggar’s bowl (kashkul), dated 18th century Iran, carried by a Sufi dervish as a sign of renouncing all worldly possessions. The upper band of inscription contains the Nad-e ‘Ali, the devotional prayer to ‘Ali. (Image: Aga Khan Museum)

In the early stages, Sufism developed into a system of mystical orders, named after their founding teachers, but tracing their spiritual genealogy to the teachings of Prophet Muhammad and Ali Ibn Abi Talib, who they considered to have been endowed with the special mission of explaining the esoteric teachings of the Qur’an. Sufi masters were known as pirs or murshids, while the followers were known as murids, and were bound to the murshid by the baya, oath of allegiance.

Access to the normative, textual Islam based on the Qur’an, hadith, fiqh (jurisprudence), tafsir (hermeneutics) required the knowledge of Arabic, restricting its appeal. The Sufi masters were able to convey Islamic teachings in local languages. The Sufi dhikrs, ceremonies in remembrance of God derived from the Qurʾānic injunction “And remember God often” (sura 62, verse 10), developed spiritual techniques that meshed with practices from local traditions such as ritual dances and controlled yoga-style breathing.

Sufism was influential in spreading Islam to sub-Saharan and West Africa in the ninth to eleventh centuries, where they spread along trade routes. Organized Sufism, however, was consolidated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, gaining ground rapidly in Asia in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions. Sufism was taken to China in the seventeenth century by Ma Laichi and other Sufis who had studied in Mecca and were influenced by the descendants of the Sufi master Afaq Khoja (1626-1694), a religious and political leader in Kashgaria (present day southern Xinjiang, China).

Manuscript of the Mathnavi of Rumi, dated 1602 Iran (Aga Khan Museum)

The mystic writings of the Persian poet Jalāl al-Dīn al-Rūmī (1207–73), also called by the honorific title Mawlānā are generally considered to be the supreme expression of Sufism. After his death, his disciples were organized as the Mawlawīyah (or Mehlevi) order, commonly known as the Whirling Dervishes due to their practice of whirling while performing the dhikr.

The Persian poet Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār Attar, who authored the finest spiritual parable in the Persian language, The Concourse of the Birds, was one of the greatest Sufi writers and thinkers, composing many brilliant prose works.

Nizari Ismailism and Persian Sufism developed a close relationship after the fall of the state of Alamut in 1256. For the first two centuries after the fall, the Imams remained inaccessible to the community in order to avoid persecution. The community concealed their identity under the mantle of Sufism without establishing formal affiliations with any particular Sufi tariqas that were spreading in Persia and Central Asia. At the same time, Sufis employed the batini tawil or esoteric teachings more widely ascribed to the Ismailis. The Nizari Ismaili Imams, who were still obliged to hide their identities, appeared to outsiders as murshids, often adopting Sufi names such as Shah Qalandar adopted by Imam Mustansir bi’llah II (d. 1480).

Sources:

Malise Ruthven, Azim Nanji, Sufi Orders 1100-1900, Historical Atlas of the Islamic World, Cartographica Limited 2004

Azim Nanji, Dictionary of Islam, Penguin Books, 2008

Sufism, Encyclopaedia Britannica (Accessed October 2015)

Compiled by Nimira Dewji

https://ismailimail.wordpress.com/2015/ ... -devotion/

Presented by the Aga Khan Council for the Southeast and Emory Muslim Student Association, Dr. Scott Kugle, associate professor at Emory, will present the topic on Sufism. You are invited to explore the historical, political, and sociological role Sufism has played within Muslim empires and dynasties. There will be time for Q&A towards the end.

www.facebook.com/events/1491721537790446/

About: Scott SIRAJ AL-HAQQ Kugle pursues research about Islamic religion and civilization especially in South Asia and the Arab World, focusing on mysticism, literature and ethics. He teaches courses on gender and sexuality in Islamic contexts. He is the author of "Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflections on Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Muslims" and other articles about contemporary identity debates regarding sexuality, diversity and Islam.

He received his PhD from Duke University in 2000 in History of Religions after graduating from Swarthmore College with High Honors in Religion, Literature, and History. His dissertation, In Search of the Center: Authenticity, Reform and Critique in Early Modern Islamic Sainthood, examined Sufism in North Africa and South Asia. His fields of expertise include Sufism, Islamic society in South Asia, and issues of gender and sexuality. He is the author of four books and numerous articles, including Sufis and Saints' Bodies: Mysticism, Corporeality and Sacred Power in Islamic Culture (UNC Press, 2007) and Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflection on Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Muslims (Oneworld Publications, 2010). He conducts research in India and Pakistan; his research languages are Arabic, Urdu, and Persian. Before coming to Emory, Kugle was an Assistant Professor of Religion at Swarthmore College and, most recently, a research scholar at the Henry Martyn Institute for Islamic Studies, Inter-Religious Dialogue, and Conflict Resolution in Hyderabad, India.

www.facebook.com/events/1491721537790446/

About: Scott SIRAJ AL-HAQQ Kugle pursues research about Islamic religion and civilization especially in South Asia and the Arab World, focusing on mysticism, literature and ethics. He teaches courses on gender and sexuality in Islamic contexts. He is the author of "Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflections on Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Muslims" and other articles about contemporary identity debates regarding sexuality, diversity and Islam.

He received his PhD from Duke University in 2000 in History of Religions after graduating from Swarthmore College with High Honors in Religion, Literature, and History. His dissertation, In Search of the Center: Authenticity, Reform and Critique in Early Modern Islamic Sainthood, examined Sufism in North Africa and South Asia. His fields of expertise include Sufism, Islamic society in South Asia, and issues of gender and sexuality. He is the author of four books and numerous articles, including Sufis and Saints' Bodies: Mysticism, Corporeality and Sacred Power in Islamic Culture (UNC Press, 2007) and Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflection on Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Muslims (Oneworld Publications, 2010). He conducts research in India and Pakistan; his research languages are Arabic, Urdu, and Persian. Before coming to Emory, Kugle was an Assistant Professor of Religion at Swarthmore College and, most recently, a research scholar at the Henry Martyn Institute for Islamic Studies, Inter-Religious Dialogue, and Conflict Resolution in Hyderabad, India.

Just as the Sufis honored all traditions, seeing each as a path leading to the highest truth, they also honored the prophets of these traditions. They looked upon each for guidance and inspiration. Many Sufis, including the great Mansur al-Hallaj, idealized Jesus as the embodiment of perfect love; they built their philosophy around him, rather than the Prophet. The renowned Sufi saint Junayd gives this prescription for Sufi practice based on the lives of the prophets:

Sufism is founded on the eight qualities exemplified by the eight prophets: The generosity of Abraham, who was willing to sacrifice his son. The surrender of Ishmael, who submitted to the command of God and gave up his dear life. The patience of Job, who endured the affliction of worms and the jealousy of the Merciful. The mystery of Zacharias, to whom God said, “Thou shalt not speak unto men for three days save by sign.” The solitude of John, who was a stranger in his own country and an alien to his own kind. The detachment of Jesus, who was so removed from worldly things that he kept only a cup and a comb—the cup he threw away when he saw a man drinking in the palms of his hand, and the comb likewise when he saw another man using his fingers instead of a comb. The wearing of wool by Moses, whose garment was woolen. And the poverty of Muhammad, to whom God sent the key of all treasures that are upon the face of the earth.

Excerpted from Rumi: In the Arms of the Beloved Translations by

Jonathan Star

Sufism is founded on the eight qualities exemplified by the eight prophets: The generosity of Abraham, who was willing to sacrifice his son. The surrender of Ishmael, who submitted to the command of God and gave up his dear life. The patience of Job, who endured the affliction of worms and the jealousy of the Merciful. The mystery of Zacharias, to whom God said, “Thou shalt not speak unto men for three days save by sign.” The solitude of John, who was a stranger in his own country and an alien to his own kind. The detachment of Jesus, who was so removed from worldly things that he kept only a cup and a comb—the cup he threw away when he saw a man drinking in the palms of his hand, and the comb likewise when he saw another man using his fingers instead of a comb. The wearing of wool by Moses, whose garment was woolen. And the poverty of Muhammad, to whom God sent the key of all treasures that are upon the face of the earth.

Excerpted from Rumi: In the Arms of the Beloved Translations by

Jonathan Star

Love Language: The Inter-Spiritual Heart of the Mystics

– From “Mira the Bee”

For decades I was conditioned to believe that to engage a mature spiritual life I needed to “pick one tradition and go deep,” which implied that my attraction to the teachings and practices at the heart of all religions was superficial and indolent. Also, that the path of non-dualism—with its affirmation of undifferentiated consciousness—was superior to my devotional disposition. Also, that my experience of longing for God was an illusion—some kind of unconscious blend of unresolved childhood abandonment and magical thinking. In other words, the energy that fueled my journey was predicated on a perfect storm of delusional inclinations.

It was only when the fire of loss swept into my life and burned the scaffolding to the ground that all conceptual constructs came tumbling down and these insidious messages revealed themselves as 1) unkind, and 2) untrue. From the ashes of grief a transfigured, more authentic self began to rise, and she felt no obligation to choose sides. She was a Jew and a Sufi, a believer and an agnostic. She practiced Vipassana and Centering Prayer, observed Shabbat and received communion. She rested in blessed moments of unitive consciousness and sang the praises of Lord Krishna.